24 Jan The Song that Ended a Strike

In October 1917 British war efforts faced a potentially paralysing challenge. Thousands of men were deserting the coal mines of southern Wales and an ugly strike over pay and living conditions was brewing. Admiralty officials estimated that the rapidly dwindling coal reserves would last another week, after which the navy would lose its ability to put ships to sea. The shores of the island would be vulnerable to attack, while vital supply routes and reinforcements to the front line would be disrupted. Even the food supplies within England would grind to a halt.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George faced a dilemma. Sending in the police and army, as had been done in the 1910-1911 riots, was not an option at this stage of the war. Going in person to appease the angry masses was more likely to have the opposite effect, providing them with a focal point for their anger and fuelling the flames of their discontent.

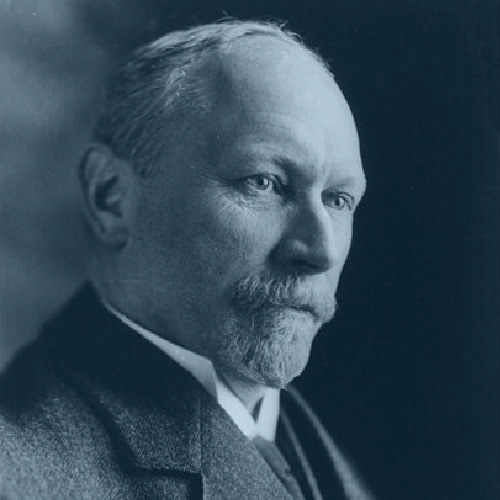

Instead, he turned to Jan Christiaan Smuts. Educated in the British-controlled Cape Colony and at Cambridge University, Smuts had been one of the most effective generals in the Afrikaaners’ fight for independence from Britain in 1899-1902, and had been instrumental in crafting the post-war peace treaty and subsequent regional, and later national, constitutions. As Minister for the Interior in the fledgling Union of South Africa, he had shown both his willingness to quash strikes ruthlessly, as well as to risk his own life in negotiating ceasefires in person.

Smuts’ exploits and acumen in the early stages of the Great War of 1914-18 lead to an invitation to join the British Imperial War Cabinet in 1917. Soon after arriving in London he had easily settled a strike by London police, followed by a more difficult intervention when thousands of munitions workers in Coventry downed tools. With trouble brewing in Wales, the Prime Minister had no hesitation in calling on Smuts to intervene. With Lloyd George’s words, “Remember, my countrymen are great singers”, echoing in his ears, Smuts headed to Wales.

On the drive from Cardiff to the coalfields Smuts encountered numerous groups of strikers, and he frequently left his car to speak with them. That evening he arrived in Tonypandy, once again the centre of trouble, where tens of thousands of angry yet curious Welshmen had gathered to listen to the man from Africa.

Looking over the sea of expectant faces, Smuts launched into a history-defining speech. “Gentlemen,” he said, “I come from far away, as you know. I do not belong to this country. I have come a very long way to do my bit in this war, and I am going to talk to you tonight about this trouble. But I have heard in my country that the Welsh are among the greatest singers in the world, and before I start, I want you first of all to sing me some of the songs of your people.”

A moment of silence met this unexpected request. Then a lone voice launched into the opening bars of the Welsh anthem, “Land of My Fathers”. More voices joined, and quickly the soul-stirring words of freedom soared over the fields, carried on the voices of ten thousand fervent men.

The land of my fathers is dear unto me,

Old land where the minstrels are honoured and free:

Its warring defenders, so gallant and brave,

For freedom their life’s blood they gave

Land!, Land!, True I am to my land!

While seas secure,

this land so pure,

o may our old language endure.

As the final echoes of the words drifted away on the breeze, Smuts leant forward and spoke with powerful simplicity. “Well, gentlemen, it is not necessary for me to say much more tonight. You know what has happened on the Western Front. You know your comrades in their tens of thousands are risking their lives. You know that the front is just as much here as anywhere else. The trenches are in Tonypandy, and I am sure you are actuated by the same spirit as your comrades in France. It is not necessary for me to add anything. You know it as well as I do, and I am sure you are going to defend the Land of your Fathers, of which you have sung here tonight, and that no trouble you may have with the Government about pay or anything else will ever stand in the way of your defence of the Land of your Fathers.”

That night Smuts addressed numerous other meetings across the coalfields in the same way. By morning the miners were at work and the threat was averted. Responding to a Cabinet enquiry on how he had settled the dispute, Smuts said simply: “The ‘Land of My Fathers’ saved us.”

That – and the wisdom of Jan Smuts. He recognised implicitly the truth in Aristotle’s exhortation that persuasion requires credibility, passion and reason. He was a man the miners would listen to. He brought them the logical argument that they were part of the British war effort and to defend their country. But the key to his success that day was his ability to put his listeners in “the right frame of mind”, a frame of mind where they would be receptive to the arguments he brought. Smuts recognised their passion, encouraged it, and then directed it. As great leaders do.

No Comments